Arty. Linocuts by Alexey Pushkarev

Artist Interviews

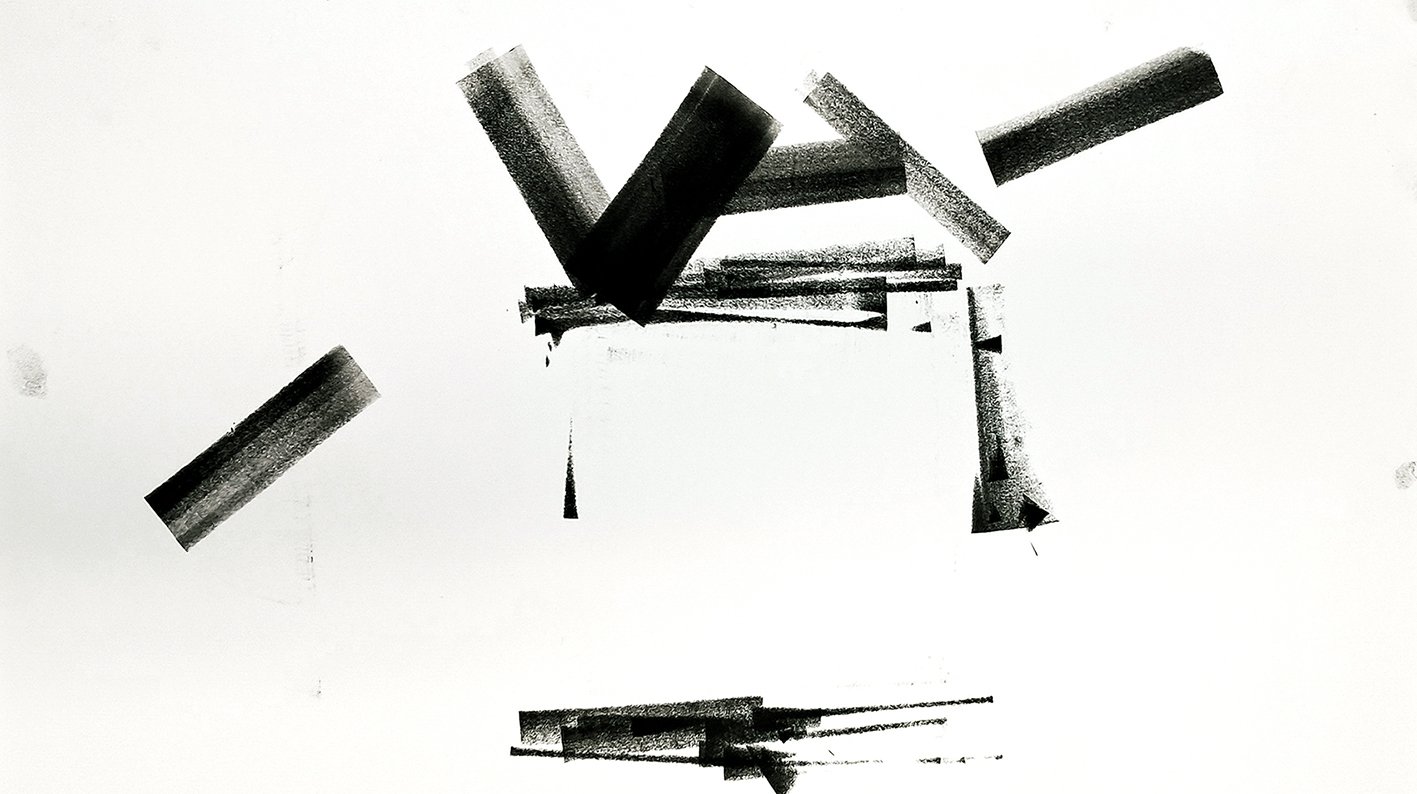

This series grew directly out of my working process with linocut. While inking the linoleum, a clean white sheet is always placed underneath to protect the surface. Its role is purely technical — it is never meant to be seen, let alone kept. During printing, the roller sometimes slips beyond the edges of the linoleum, leaving accidental marks on this white sheet. Normally, these sheets are simply thrown away.

At a certain point, I stopped and questioned this habit. These marks were not mistakes; they were traces of the process itself — quiet evidence that something had already happened. I began to see them as fragments of unfinished stories, carrying the energy of the act of printing.

This moment of reconsideration became the foundation of Reborn. What was destined for the bin was given a second life. The series consists of ten original sheets, each shaped by chance, movement, and repetition. The compositions are not planned in advance; they emerge naturally from the process, preserving its spontaneity and unpredictability.

In many ways, linocut itself is an act of rebirth. You begin with a blank piece of linoleum, and through carving, you remove what will never print. The process is intimate and slightly secretive, and the final result can never be fully controlled. Each print carries subtle differences, shaped by pressure, ink, and chance.

Reborn is a reflection on transformation — of material, of intention, and of perception. It is about noticing what usually goes unseen and allowing it to become something meaningful.

Artist and printmaker Alexey Pushkarev came to Melbourne from Moscow during the coronavirus pandemic and started his life in Australia in a quarantine hotel. He says he quickly found his own community of linocut artists. In this podcast, Alexey talks about working with linoleum, a process he compares to meditation, “an intimate dialogue between the artist and the material.”

Alexey's artworks can be seen at the Linden Postcard Show 2025, which will run until November 2, as well as at the PULSE exhibition at the Art Lovers Gallery from October 10 to December 20.

Irina:

A couple of weeks ago, I happened to visit the Postcard Show exhibition at Linden Gallery in St Kilda, and there I saw your wonderful print — a recognisable Melbourne scene, but done entirely in your own style.

How did you end up at the Linden Postcard Show?

Alexey:

Good question. I got there quite by chance, actually, through my community, Firestation Print Studio — a place where I usually make my prints. Sometimes I meet other artists there; we gather once a month and print together. Someone said to me, “Alexey, your work is fantastic — there’s an upcoming show at Linden Gallery, you should submit.

” I thought, why not? So I sent two of my works. One shows a classic, iconic view of Melbourne, and the other is a bit more abstract, but not entirely so.

Irina:

Let’s tell our listeners a bit more about you. Alexey Pushkarev has lived in Melbourne for about four years now. He moved here during COVID, after living in Moscow, where he was an Art Director at National Geographic Traveler, OK! Magazine, and GQ Magazine. He worked for the Condé Nast publishing group in very senior roles. And now you find yourself in Australia — tell us about your journey here.

Alexey:

It was a long journey. Everything that came before — I sometimes call it another life. Arriving in Melbourne meant entering a completely different world, a different rhythm and lifestyle.

Before this, I worked for many years in the graphic design industry. I was always surrounded by design, inspired by it. But originally, I studied fine arts — I graduated from the Ivan Fyodorov Printing University as a Book Illustrator. I worked with book design, printing, and painting. That was my foundation, what really shaped me. When I came here, I tried to find myself again through design — it was easier to connect in that field. Art takes more time and community to grow into, so design came first. But art was always calling me back. I always wanted to return, to create, to carve, to print again.

Irina:

So it all began with book illustrations?

Alexey:

Yes, everything started around the year 2000. It’s a funny story — even choosing my university was a kind of accident. I was into art, but didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. My parents suggested applying to the local Printing University. I applied — and was lucky enough to get in. There, I joined a printmaking studio called “Etching Studio,” and that place truly shaped me. I worked as a training master there, while still studying. That studio gave me everything — my passion, my inspiration, my love for printmaking.

Irina:

And now, if someone visits your website, alexeypushkarev.com, they can see your prints — especially your linocuts, which often depict Australian symbols, both natural and architectural. Tell us about the method you work with — what is linocut?

Alexey:

Linocut is a printing technique. It dates back roughly to the early 20th century. Initially, it was, I think, the late 19th century. Then people lost interest in it. But in the early 20th century, it was revived. The founders of my university revived linocut technique and formed the Favorsky Institute. Vladimir Favorsky was a great artist and engraver.Yes, I use linoleum in my printing method. I carve out the white space with special tools on the linolium surface. It is a type of printing where what you carve out is white, and what remains on top is uncut. Ink is applied onto the surface, and it is printed. It is a very interesting technique.

Irina:

So what we see as black is what was on top, what you did not carve out, and the white areas are what you carved out.

Alexey:

Yes, the white is exactly what I carve out with tools, achieving different lines and dots with different tools. Texture. Yes, it is a kind of form, probably a relief. Maybe somewhat like sculpture, you could say. Because when you touch it, it is quite a relief thing. Yes, it’s such a technique.

Irina:

And often, there appears some bright colour in your prints.

Alexey:

Probably it comes from my inspiration by artists who influenced me a bit, and it manifests in these dots, in some signs. Mostly, of course, I like black and white. It is stricter, more emotional, saturated. Colour livens it up a bit, but yes, I tried to find a symbiosis, and I always have some sign, a small dot, a small colour element that always makes you think about something.

Irina:

An accent.

Alexey:

Yes, an accent. A certain accent makes a small point in the work.

Irina:

I allowed myself to translate your website status into Russian. I’m going to read it now. On your website, you describe linocut beautifully. You say: “ For me, linocut is more than just a technique. It is a language of contrasts, textures, and stories waiting to be told. A rhythmic process of carving, inking, and pressing. Can I say it like that? Pressing.

Alexey:

Well, yes.

Irina:

It is, in itself, a meditation — an intimate dialogue between the artist and the material. I’m drawn to its tactile nature, to how a simple piece of linoleum transforms into something alive and full of meaning. Every print is a reflection of patience and determination, from the first sketch to the final impression. Every stage is intentional, every detail carries a personal touch.

You also wrote that relief printing is a ritual — a way to translate emotions into something tangible. You were just talking about a point from which everything begins. And that very point, the one everything starts with, is also what your website begins with, a quote by Wassily Kandinsky. When I looked at your works, it seemed to me that dots play a special role there. Also, there appears to be a reference to Australian dot painting.

I think that’s the Shrine of Remembrance, right? Those red dots around it — on one hand, they resemble Australian painting, and on the other, they seem to reference the poppy flower, right?

Alexey:

Yes

Irina:

And there are those red dots around it, and these red dots, on the one hand, resemble Australian painting, and on the other hand, they seem to reference the poppy flower, right? The one associated with the Shrine. And at the same time, I don’t know — it feels a bit like the Aboriginal flag too, with that large circle.

When you arrived in Australia, how did you first encounter Aboriginal art? Did it influence you in any way?

Alexey:

For me, it was like discovering an entirely different world — something new and deeply sincere. And this method — using dots, drawing with dots, and the idea that a dot is the foundation — naturally influenced me, because it felt close. Everything truly begins with a dot. When you start planning a piece, it begins the moment you sit down in front of a blank sheet, a blank plate, a piece of linoleum. At first, you just sit, almost meditating, thinking about what you want to express. Everything starts from that very point — the starting point. And of course, it influenced me. That’s a good question about observations from nature. Because when I arrived in Melbourne, everything was new — different nature, different flowers, different air, different animals.

Everything was different. Naturally, I wanted to capture it all. In the beginning, when we moved here, we travelled around, rode our bikes, took photos — and later those photos became my inspiration. I turned them into linocuts.

Irina:

I remember clearly the moment we arrived in Australia. On the first day, we had jet lag, and we woke up while it was still dark. On the second day, the same. But on the third day, we woke up, and it was already light. We were staying in an Airbnb where, on the ground floor, there was a small courtyard. And in that courtyard, there were these flowers called Birds of Paradise. Yes. And today, when I looked at your works, I noticed you have a drawing of these very flowers — Birds of Paradise. It looked like watercolour, yes?

Alexey:

No, actually it’s a drawing, more of a graphic work — but yes, it’s a drawing. Again, it was inspired by that moment, because once we were biking and I saw those unusual Bird of Paradise flowers, and we photographed them. I keep coming back to them because they have such a graphic shape, such an interesting texture — they look almost otherworldly.

Irina:

But when I looked at your drawing of the Bird of Paradise, it seemed to me that the lines, the circles, the dots surrounding the flowers reminded me of Aboriginal art. And I’m trying to understand — is this my own projection, am I imagining it, or do you consciously incorporate those references?

Alexey:

I think they appear intuitively. Because when we arrived here, of course, we went to museums, we went to NGV, we looked at classical Aboriginal art — and it left a mark on me. It left an imprint that later emerged subconsciously. Aboriginal art influenced me, and it appears in almost every one of my works in some form — in the dot, in the line.

Irina:

And among the iconic Australian places that become the main subjects of your works — the Opera House, Rippon Lea Estate, the Anzac Memorial, the Spirit of Tasmania, that famous ship I see almost every day, Cook’s Cottage, the Royal Exhibition Building, the Shrine of Remembrance — and also places that may not be architecturally famous but are still very recognizable in the Melbourne landscape, like the bicycle against those wooden pylons sticking out of the water. How do you choose what you want to draw? What kind of connection do you need to have with a place to decide to make a print?

Alexey:

History. That’s probably the main thing. It needs to be a place with history, something iconic. Because when I first started making prints here, I wanted to show my work, and naturally, I wanted to learn about the historic places. Not just lifestyle scenes — I wanted that sense of symbolic importance, because symbols matter.

Rippon Lea — the emotion of walking through it, the beauty of the garden around it. It’s about the feeling that the garden evokes. And the architecture is completely different from what I knew. Again, nothing like what we had in Russia. So naturally it was something new — and that’s what drew me to the Spirit of Tasmania. It’s more like a dream. A dream to someday travel on that ship. It hasn’t happened yet — maybe one day. And that dream was something I wanted to reflect in my work.As for the bicycle, that linocut was a combination of the bicycle we used while travelling, and that historic pier in Port Melbourne.

Irina:

Your next exhibition is soon, right?

Alexey:

Yes — please tell us about it.

Irina:

It opens on October 10th, right?

Alexey:

Yes, that will be my next exhibition — a group exhibition featuring two of my new linocuts. The theme is pulse and vibration. The core idea of the exhibition is abstraction — patterns and rhythms that appear in the artist's work. Linocut expresses this beauty fully for me, because the carved linescreate a kind of rhythm. And my two pieces fit perfectly — both depict Australian plants that, among all this rhythm and chaos, act as the foundation, the anchor.

Irina:

I was just thinking — when you look at the Australian landscape, the bush, in some way, it aligns with what you’re saying. It’s like these drawn lines — some deeper and further away, some closer — line and depth, line and volume.

Alexey:

Yes, depth is very important. Just yesterday, going to work, I saw a field with a single dead tree standing in the middle. It looked incredibly graphic against the empty landscape. In the distance, there were lush green trees, but this one stood right in front of you — so emotional, so poetic. It stayed strong, saturated, dried out, yet still existing, carrying meaning.

Irina:

Like all dead forests.

Alexey:

That eventually regenerates.

Irina:

Yes, they regenerate.

Alexey:

After a tree dries out, you wait for rebirth. And this influenced one of my series, which I called “Rebirth.” When you apply ink to the linoleum, to keep the space clean, you place a white sheet underneath. Sometimes the roller slips off the linoleum and leaves a mark on that white sheet. Technically, these sheets are just trash — you throw them away. But I thought — why not? These are traces of art that could be transformed into something else. This is how my series “Rebirth” was created — ten sheets that seemed destined for the bin, but instead became a special, emotional series. And in a way, linocut itself is a kind of rebirth — you start with a blank piece of linoleum, and it’s such an intimate process, a bit secretive, a bit unexpected. As you carve out the hite areas, the final print may come out slightly different. But during the process, when you search for the line — how to express it, how to angle the tool — it’s an intimate process, and you never fully know what the result will be. Of course, technically, you understand what you’re doing, but there is always some detail that later reveals itself and shows you something new. And the work hanging at Linden Art — it hangs above this very piece.

Irina:

It looks quite abstract, right?

Alexey:

Abstract in a way.

Irina:

In green or orange?

Alexey:

No, no — it seems abstract, but in fact it was inspired by a portrait of my beloved half — my wife. We were imply sitting at home; I was drawing, and Dina, my wife, was doing her own thing. I saw that moment, captured it in a photo, and drew it. Originally it was a portrait, but the final result became an abstraction in which every viewer can see something different.

Irina:

I guess I’ll need to visit the exhibition again to look more closely.

Alexey:

It’s very interesting — someone once told me, “Oh, I see a whale in this.” It was fascinating to hear what friends, colleagues, and visitors saw — something entirely different each time. Everyone brings their own perception. That’s the beauty of it — the intimacy of the process, where you try to express something of your own, and others bring their own nterpretations.

Irina:

It becomes a kind of co-creation.

Alexey:

Yes, a form of co-creation.

Irina:

Thank you so much, Alexey. It was a pleasure to meet you. The exhibition at Linden New Art Gallery is on now — it’s called the Postcard Show. You can see two of the works there. And the second exhibition we discussed opens very soon — on October 10th at Art Lovers Gallery in Collingwood.

Alexey:

It will be a completely different story, but also very interesting, revealing something entirely new.

Irina:

Thank you, and I hope you’ll allow us to include a few images in the podcast description so listeners can see what we were talking about.

Alexey:

Of course, with pleasure. I’ll provide everything. And thank you for the opportunity to talk, to meet the listeners, to meet you, Irina.

Irina:

It was a great pleasure.

Alexey:

The pleasure is mutual. Thank you so much.

Rebirth

This series grew directly out of my working process with linocut. While inking the linoleum, a clean white sheet is always placed underneath to protect the surface. Its role is purely technical — it is never meant to be seen, let alone kept. During printing, the roller sometimes slips beyond the edges of the linoleum, leaving accidental marks on this white sheet. Normally, these sheets are simply thrown away.

At a certain point, I stopped and questioned this habit. These marks were not mistakes; they were traces of the process itself — quiet evidence that something had already happened. I began to see them as fragments of unfinished stories, carrying the energy of the act of printing.

This moment of reconsideration became the foundation of Reborn. What was destined for the bin was given a second life. The series consists of ten original sheets, each shaped by chance, movement, and repetition. The compositions are not planned in advance; they emerge naturally from the process, preserving its spontaneity and unpredictability.

In many ways, linocut itself is an act of rebirth. You begin with a blank piece of linoleum, and through carving, you remove what will never print. The process is intimate and slightly secretive, and the final result can never be fully controlled. Each print carries subtle differences, shaped by pressure, ink, and chance.

Reborn is a reflection on transformation — of material, of intention, and of perception. It is about noticing what usually goes unseen and allowing it to become something meaningful.

Nothing truly ends; it transforms.

Original Linocut Artwork Series by Alexey Pushkarev

Contemporary Printmaking • Original Linocut Prints • Artist Practice

Reborn is an original linocut artwork series by Alexey Pushkarev, a contemporary printmaking artist working with hand-carved linoleum and experimental processes. The series explores transformation, material memory, and rebirth through the physical act of printmaking.

This body of work emerged directly from my linocut printing process. While inking the linoleum, a clean white sheet is placed underneath to protect the surface. Its function is purely technical — it is never meant to be seen and is usually discarded. During printing, the roller occasionally slips beyond the edges of the linoleum, leaving accidental marks on this white sheet.

Rather than viewing these marks as waste, I began to see them as traces of the process itself — visual records of movement, pressure, and time. These accidental impressions became the starting point for Reborn, transforming discarded materials into original artworks.

The series consists of ten unique linocut prints, each shaped by chance and repetition. No composition is pre-planned. The works retain the unpredictability that defines contemporary printmaking, where each print differs subtly from the last.

Red and blue form the central visual language of the series. These two elements interact, separate, and reunite, suggesting balance, tension, and continuity. Together, they point toward the future — not as a fixed outcome, but as an evolving state.

Linocut, as a medium, embodies the idea of rebirth. Each work begins with a blank piece of linoleum. As material is carved away, the image slowly emerges. The process is intimate, physical, and slightly secretive. Ink, pressure, and hand movement ensure that no two prints are ever identical.

Reborn reflects my broader artist practice — an exploration of transformation through contemporary printmaking. It invites the viewer to reconsider what is usually unseen and to find value in traces left behind.